Modern societies run on power, not mere energy. Power is energy per unit time, or force times speed. We aren't interested in driving as fast as we run, or in phone calls that take a day to go through. We also don't like sitting in the dark, while food is getting warm in the refrigerator, only because our outlets ran out of juice. In short, we crave for power that is just there, waiting for us to be used at will. And, yes, most environmentalists have similar sentiments.

But, there is a price to pay for our cravings. No, I am not speaking about carbon dioxide emissions or mercury in the fish we eat. Hardly anyone cares about such things anymore. I am talking about our utter, total reliance on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, with large dams providing a thin icing on a huge power cake. You see, renewables can produce a lot of energy, but never enough power, 24/7, and when we want it. This is the discovery the impatient people and their governments are making in 2012.

Excessive power that runs our power-hungry society is expensive. But just how expensive? I have tried to answer this question using the lovely Index Mundi website with a large selection of global commodity prices, the EIA database for petroleum and natural gas consumption in the U.S., and the BP statistical review of world energy for the U.S. coal production. To normalize all prices, I have used the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to account for inflation.

I have chosen the year 1983 to reference the U.S. dollar value as one. In January 1983, I started working for Shell Development as a young researcher. That life-changing experience converted me into a petroleum engineer for good. Each dollar I earned then is equal to 2.3 dollars today. So much for low inflation in the deregulated, booming global economy.

I have used the West Texas Intermediate and Brent crude oil prices since August 1982, to determine the upper limit of petroleum cost in the U.S. For natural gas, I have used the Henry Hub prices and the Russian prices since August 1991 (earlier price data were unavailable for Henry Hub). For coal, I have used the Australian thermal coal prices, understanding the the top secret U.S. prices might have been up to 10 - 30 percent lower, because of the huge captive coal supply in Western U.S. This coal price differential has probably disappeared by 2011. But I don't know for sure.

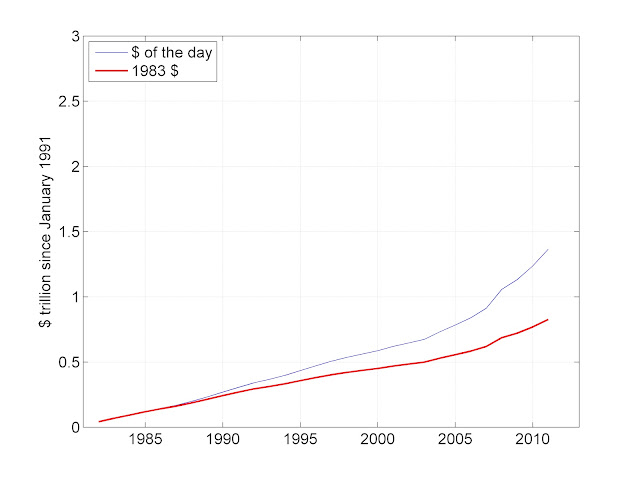

Below, there are twelve charts. The first five charts are for crude oil, the next five for natural gas, and the final two for coal. The monthly bill charts show the rates of expenditures, and the cumulative charts show total expenditures from a starting date. All cumulative curves, but those for natural gas paid for with Henry Hub prices, are hockey sticks, increasing very rapidly (curving up quickly) in recent years, despite the global recession.

Let's start from petroleum, as it is by far the largest cost of powering the U.S. society. After the almost instantaneous downward price correction in late 2008 and 2009, the price of oil resumed its pre-2008 growth, saturating at a somewhat lower level than the all-time peak. The monthly bills in 2011 and 2012 have been suppressed mostly by a significant destruction of demand for petroleum products: The demand for 1.6 million barrels of crude oil per day disappeared in the U.S. between 2008 and 2012.

The roughly 11 trillion constant dollars of total debt, accumulated in the U.S. since 1982, are 2.5 times more than the 4.3 trillion constant dollars we paid for crude oil in either of the two reference prices. The actual expenditures for crude purchases in the U.S. were less because several lower quality, heavy and sour crudes from Venezuela, California, and Canada are priced lower. One could argue that we have subsidized our love for Camaros, suburbs, Hummers, F150s, highways, Ford Excursions, more highways, exurbs, etc. by borrowing from the world and printing paper dollars.

On an energy-equivalent basis, natural gas should be roughly 6 times cheaper than oil. Therefore, today, 1,000 standard cubic feet (mcf) of gas, should cost roughly the price of one barrel of oil divided by six, or 17 dollars per mcf. At $3 per mcf, natural gas in the U.S. is 5 times cheaper than oil, in contrast to Europe or Asia.

Today, the U.S. monthly expenditures for natural gas are as high as they were in 2002, even though we consume 1 trillion standard cubic feet (Tcf) of gas more. The discovery and production of unconventional natural gas allowed for this incredible achievement; the only exception to the global trend of ever more expensive fossil power.

Since 2008, the cumulative cost of natural gas in the U.S. has been less by 560 billion dollars of the day (256 billion constant dollars), compared with the cost of natural gas exported by Russia. One might say that the savings on natural gas alone paid for much of the two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. One might also say that the current better shape of U.S. economy relative to the E.U. is the result of cheaper natural gas (and coal).

Natural gas production in the U.S. is a phenomenal success story, one that dwarfs the ever-fashionable iPhone. So whenever you feel like hating "fracking," please stop and reflect on the fact that you might have a job only because hydrofracturing has been so successful in the recovery of natural gas and - now- light oil.

Coal has always been dirt-cheap in the U.S. Still, the total bill for U.S. coal could be as high as 800 billion constant dollars since 1982. Today, natural gas is cheaper than coal in the U.S., and the natural gas-fired power plants are several times cheaper than the coal-fired ones.

In summary, easy cheap oil is gone and oil price must grow, while demand is destroyed. Cheap surface coal is also limited worldwide, and coal price will continue to grow. Everywhere, but in the U.S., the price of natural gas has been increasing as well. Cheap unconventional gas in the U.S. is the miracle energy source that saved us from a lot worse recession to the tune of 600 billion dollars of the day, and probably twice that amount in American jobs created and saved from disappearance.

The lower carbon dioxide and mercury emissions in the U.S. result from natural gas displacing coal in electricity generation. Also, we have lowered oil consumption by 1.6 million barrels of oil per day compared with the amount of oil we were burning daily just four years ago. Burning less oil means lower carbon dioxide emissions. We still have a long way to go to decrease fossil fuel consumption in the U.S. to the per capita level of industrialized Europe.

P.S. A couple of illustrations of the points made here were published in the September 15 New York Times. An increase of gasoline prices in August 2012, pushed consumer prices up by 0.6 percent, at the fastest rate in more than three years. That it must have happened follows for example from the second chart, with the cumulative oil cost hockey stick curving up. Higher prices of fuels equal depressed economic activity and that's what happened. Production at the U.S. factories, mines and utilities dropped 1.2 percent in August, the biggest decline since August 2009.

The United States still has cheap natural gas to prevent it from slipping into an outright recession; but not so in Japan. While Japan is setting a policy to phase out nuclear power by 2040, its cost of delivering power to the population and industry has skyrocketed:

"[The] Keidanren business federation and others have insisted that the higher energy costs are crippling the country’s economy. Tokyo Electric, Japan’s largest utility and the operator of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, has increased rates for both homes (an average of more than 8 percent) and businesses (an average of about 15 percent).

Business leaders warn that such costs will prompt more companies to move their operations overseas. And costly fuel imports already contributed last year to Japan’s first annual trade deficit in more than 30 years and made the nation more dependent on oil and natural gas from the volatile Middle East and Russia."

(By Hiroko Tabuchi)

Interestingly, a day later (9/16/2012) , the same Mr. Hiroko Tabuchi reported that Japan wouldn't stop work on nuclear reactors.

The Japanese society is at a fork: It can either deindustralize and live with much less power, or it must use nuclear power to keep on the current path. The same fork is awaiting Germany, which declared their phase out of nuclear power (26 percent of electricity) by 2026.

We have entered an interesting period of history. Given the exploding cost of continuous power in money and biological survival, developed societies will have to make clear moral and political choices, and live with the consequences of theses choices for decades or centuries.

"Clean" power (not energy!) means a very, very different world with many fewer people. But I have already written on this subject; see, for example, this or this or this or this, or a dozen other blog entries.

P.S.P.S. Here is a thoughtful comment I got via email on 09/30/2012:

|

| Two tons of American love of power, including 450 pounds of human payload. Source: Don Petersen for The New York Times, September 14, 2012. |

Excessive power that runs our power-hungry society is expensive. But just how expensive? I have tried to answer this question using the lovely Index Mundi website with a large selection of global commodity prices, the EIA database for petroleum and natural gas consumption in the U.S., and the BP statistical review of world energy for the U.S. coal production. To normalize all prices, I have used the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to account for inflation.

I have chosen the year 1983 to reference the U.S. dollar value as one. In January 1983, I started working for Shell Development as a young researcher. That life-changing experience converted me into a petroleum engineer for good. Each dollar I earned then is equal to 2.3 dollars today. So much for low inflation in the deregulated, booming global economy.

I have used the West Texas Intermediate and Brent crude oil prices since August 1982, to determine the upper limit of petroleum cost in the U.S. For natural gas, I have used the Henry Hub prices and the Russian prices since August 1991 (earlier price data were unavailable for Henry Hub). For coal, I have used the Australian thermal coal prices, understanding the the top secret U.S. prices might have been up to 10 - 30 percent lower, because of the huge captive coal supply in Western U.S. This coal price differential has probably disappeared by 2011. But I don't know for sure.

Below, there are twelve charts. The first five charts are for crude oil, the next five for natural gas, and the final two for coal. The monthly bill charts show the rates of expenditures, and the cumulative charts show total expenditures from a starting date. All cumulative curves, but those for natural gas paid for with Henry Hub prices, are hockey sticks, increasing very rapidly (curving up quickly) in recent years, despite the global recession.

Let's start from petroleum, as it is by far the largest cost of powering the U.S. society. After the almost instantaneous downward price correction in late 2008 and 2009, the price of oil resumed its pre-2008 growth, saturating at a somewhat lower level than the all-time peak. The monthly bills in 2011 and 2012 have been suppressed mostly by a significant destruction of demand for petroleum products: The demand for 1.6 million barrels of crude oil per day disappeared in the U.S. between 2008 and 2012.

The roughly 11 trillion constant dollars of total debt, accumulated in the U.S. since 1982, are 2.5 times more than the 4.3 trillion constant dollars we paid for crude oil in either of the two reference prices. The actual expenditures for crude purchases in the U.S. were less because several lower quality, heavy and sour crudes from Venezuela, California, and Canada are priced lower. One could argue that we have subsidized our love for Camaros, suburbs, Hummers, F150s, highways, Ford Excursions, more highways, exurbs, etc. by borrowing from the world and printing paper dollars.

On an energy-equivalent basis, natural gas should be roughly 6 times cheaper than oil. Therefore, today, 1,000 standard cubic feet (mcf) of gas, should cost roughly the price of one barrel of oil divided by six, or 17 dollars per mcf. At $3 per mcf, natural gas in the U.S. is 5 times cheaper than oil, in contrast to Europe or Asia.

Today, the U.S. monthly expenditures for natural gas are as high as they were in 2002, even though we consume 1 trillion standard cubic feet (Tcf) of gas more. The discovery and production of unconventional natural gas allowed for this incredible achievement; the only exception to the global trend of ever more expensive fossil power.

Since 2008, the cumulative cost of natural gas in the U.S. has been less by 560 billion dollars of the day (256 billion constant dollars), compared with the cost of natural gas exported by Russia. One might say that the savings on natural gas alone paid for much of the two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. One might also say that the current better shape of U.S. economy relative to the E.U. is the result of cheaper natural gas (and coal).

Natural gas production in the U.S. is a phenomenal success story, one that dwarfs the ever-fashionable iPhone. So whenever you feel like hating "fracking," please stop and reflect on the fact that you might have a job only because hydrofracturing has been so successful in the recovery of natural gas and - now- light oil.

Coal has always been dirt-cheap in the U.S. Still, the total bill for U.S. coal could be as high as 800 billion constant dollars since 1982. Today, natural gas is cheaper than coal in the U.S., and the natural gas-fired power plants are several times cheaper than the coal-fired ones.

In summary, easy cheap oil is gone and oil price must grow, while demand is destroyed. Cheap surface coal is also limited worldwide, and coal price will continue to grow. Everywhere, but in the U.S., the price of natural gas has been increasing as well. Cheap unconventional gas in the U.S. is the miracle energy source that saved us from a lot worse recession to the tune of 600 billion dollars of the day, and probably twice that amount in American jobs created and saved from disappearance.

The lower carbon dioxide and mercury emissions in the U.S. result from natural gas displacing coal in electricity generation. Also, we have lowered oil consumption by 1.6 million barrels of oil per day compared with the amount of oil we were burning daily just four years ago. Burning less oil means lower carbon dioxide emissions. We still have a long way to go to decrease fossil fuel consumption in the U.S. to the per capita level of industrialized Europe.

|

| Since August 1991, the cumulative bill for natural gas purchases at the Henry Hub prices has been up to 1.7 trillion dollars of the day and 1 trillion of the 1983 dollars. |

|

| Since August 1991, the cumulative bill for natural gas purchases at the Russian prices has been up to 2.4 trillion dollars of the day and 1.2 trillion of the 1983 dollars. |

P.S. A couple of illustrations of the points made here were published in the September 15 New York Times. An increase of gasoline prices in August 2012, pushed consumer prices up by 0.6 percent, at the fastest rate in more than three years. That it must have happened follows for example from the second chart, with the cumulative oil cost hockey stick curving up. Higher prices of fuels equal depressed economic activity and that's what happened. Production at the U.S. factories, mines and utilities dropped 1.2 percent in August, the biggest decline since August 2009.

The United States still has cheap natural gas to prevent it from slipping into an outright recession; but not so in Japan. While Japan is setting a policy to phase out nuclear power by 2040, its cost of delivering power to the population and industry has skyrocketed:

"[The] Keidanren business federation and others have insisted that the higher energy costs are crippling the country’s economy. Tokyo Electric, Japan’s largest utility and the operator of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, has increased rates for both homes (an average of more than 8 percent) and businesses (an average of about 15 percent).

Business leaders warn that such costs will prompt more companies to move their operations overseas. And costly fuel imports already contributed last year to Japan’s first annual trade deficit in more than 30 years and made the nation more dependent on oil and natural gas from the volatile Middle East and Russia."

(By Hiroko Tabuchi)

Interestingly, a day later (9/16/2012) , the same Mr. Hiroko Tabuchi reported that Japan wouldn't stop work on nuclear reactors.

The Japanese society is at a fork: It can either deindustralize and live with much less power, or it must use nuclear power to keep on the current path. The same fork is awaiting Germany, which declared their phase out of nuclear power (26 percent of electricity) by 2026.

We have entered an interesting period of history. Given the exploding cost of continuous power in money and biological survival, developed societies will have to make clear moral and political choices, and live with the consequences of theses choices for decades or centuries.

"Clean" power (not energy!) means a very, very different world with many fewer people. But I have already written on this subject; see, for example, this or this or this or this, or a dozen other blog entries.

P.S.P.S. Here is a thoughtful comment I got via email on 09/30/2012:

John

H. King, Jr.

2517 Rhonda. Dr.

Vestal, NY 13850

E-mail at: zeropoint1@earthlink.net

Subject: Your Blog on Fossil Fuels and U.S.

Dear Professor Patzek,

I'm writing you directly as I was not able to post my comments to your LifeItself Blogspot website. Thank you for a very necessary, informative and clear presentation. Unfortunately, it seems that few people, especially politicians, "get it" as yet. Most everyone in denial or too scary to contemplate or both? Now, here's a few of my thoughts.

I have one basic question which is: why is "fracked" N-gas today so much cheaper in constant $ / BTU compared to Coal, Brent, WTI, Russian N-gas and all the other fossil fuels? Is it that the Net Energy or equivalently the EROI of "fracked" N-gas is very much better than that of all the other current fossil fuels? If that is the case, why? It would not seem that just the improved efficiency of the drilling and "fracking" mechanisms could make such a big difference. Could it be that the effective energy density of N-gas due to the very high pressures at 6,000 ft. and deeper is as high or even higher than that of liquid petroleum in the ground? How else can the implied EROI be so high? Now a few of my own comments and observations.

In your first paragraph you note that "Modern societies run on power, not mere energy." That is, though globally energy flow (power) is more or less continuous power consumption at the local level is highly variable. And, as you further note, that fact has fundamental consequences when considering alternative sources of energy which fundamentally cannot provide continuous flows of energy even from large concentrated sources though potentially, on average, at a global scale more or less. Yet, this problem already existed to some degree at the very beginnings of the use of wood from the forests for fires by early man, continued through to the beginnings of and through the age of coal and, as you note, it still exists to this day with the use of all the fossil fuels. Because the production and transport of the energy carriers (fossil fuels) from and across the ground is fundamentally somewhat intermittent or at least a variable process there is the need for storage of vast amounts of the energy carriers, the equivalent of energy storage. This has always been necessary and continues to be a fundamental necessity to this day. Indeed, consider all the piles of coal and the various "tank farms" storing N-gas, raw petroleum and finished petroleum products.

As you note, the introduction of new intermittent sources of produced energy flow (power) such as Wind Power and Solar Power will likely require even more vast amounts of energy storage in order to be able to meet the variable rates of power demand required by almost all the various consumers at local levels. And, it's not just that the amount of energy storage that probably will have to be significantly greater but this new requirement for energy storage will require new technologies for creating stored energy from the energy flow from mostly electric power, something we do today on only very small scales, such as with the batteries in Hybrid cars, batteries for cell phones, iPhones, iPads and etc. And, every conversion of power to stored energy or the conversion of stored energy to (electric) power has its various significant inefficiencies. The worst (lowest) efficiencies, »0.3 - »0.4, are associated with heat engines and the highest efficiencies, »0.90 - »0.97, are associated with batteries and electrical machinery. But how much lithium and other rare earth elements or chemical compounds suitable as electrolytes and such is available for making great numbers giant batteries? And, what other energy storage and/or production technologies could be developed that don't involve the use of inefficient heat engines? Building and maintaining all this supporting infrastructure will necessarily consume an additional very large amount energy.

Therefore, there is certainly a very great amount of new energy infrastructure based on new energy (power) producing technology that will be necessary to be developed and built to the necessary large scales along with a vast new energy storage infrastructure to support the worlds modern high energy intensity civilizations in the future. Creating and maintaining all this new infrastructure will necessarily require a very significant additional energy expenditure. The $64 x 1012 question: can all this be accomplished in time to avoid a catastrophic collapse of the world's modern civilizations with the net energy from the fossil fuels that still remain accessible? The alternative is too horrific to even contemplate!

No need to reply directly but I thought you might want to consider these issues and questions in a bit more detail in one of your future Blog postings.

Best regards, John King

2517 Rhonda. Dr.

Vestal, NY 13850

E-mail at: zeropoint1@earthlink.net

Subject: Your Blog on Fossil Fuels and U.S.

Dear Professor Patzek,

I'm writing you directly as I was not able to post my comments to your LifeItself Blogspot website. Thank you for a very necessary, informative and clear presentation. Unfortunately, it seems that few people, especially politicians, "get it" as yet. Most everyone in denial or too scary to contemplate or both? Now, here's a few of my thoughts.

I have one basic question which is: why is "fracked" N-gas today so much cheaper in constant $ / BTU compared to Coal, Brent, WTI, Russian N-gas and all the other fossil fuels? Is it that the Net Energy or equivalently the EROI of "fracked" N-gas is very much better than that of all the other current fossil fuels? If that is the case, why? It would not seem that just the improved efficiency of the drilling and "fracking" mechanisms could make such a big difference. Could it be that the effective energy density of N-gas due to the very high pressures at 6,000 ft. and deeper is as high or even higher than that of liquid petroleum in the ground? How else can the implied EROI be so high? Now a few of my own comments and observations.

In your first paragraph you note that "Modern societies run on power, not mere energy." That is, though globally energy flow (power) is more or less continuous power consumption at the local level is highly variable. And, as you further note, that fact has fundamental consequences when considering alternative sources of energy which fundamentally cannot provide continuous flows of energy even from large concentrated sources though potentially, on average, at a global scale more or less. Yet, this problem already existed to some degree at the very beginnings of the use of wood from the forests for fires by early man, continued through to the beginnings of and through the age of coal and, as you note, it still exists to this day with the use of all the fossil fuels. Because the production and transport of the energy carriers (fossil fuels) from and across the ground is fundamentally somewhat intermittent or at least a variable process there is the need for storage of vast amounts of the energy carriers, the equivalent of energy storage. This has always been necessary and continues to be a fundamental necessity to this day. Indeed, consider all the piles of coal and the various "tank farms" storing N-gas, raw petroleum and finished petroleum products.

As you note, the introduction of new intermittent sources of produced energy flow (power) such as Wind Power and Solar Power will likely require even more vast amounts of energy storage in order to be able to meet the variable rates of power demand required by almost all the various consumers at local levels. And, it's not just that the amount of energy storage that probably will have to be significantly greater but this new requirement for energy storage will require new technologies for creating stored energy from the energy flow from mostly electric power, something we do today on only very small scales, such as with the batteries in Hybrid cars, batteries for cell phones, iPhones, iPads and etc. And, every conversion of power to stored energy or the conversion of stored energy to (electric) power has its various significant inefficiencies. The worst (lowest) efficiencies, »0.3 - »0.4, are associated with heat engines and the highest efficiencies, »0.90 - »0.97, are associated with batteries and electrical machinery. But how much lithium and other rare earth elements or chemical compounds suitable as electrolytes and such is available for making great numbers giant batteries? And, what other energy storage and/or production technologies could be developed that don't involve the use of inefficient heat engines? Building and maintaining all this supporting infrastructure will necessarily consume an additional very large amount energy.

Therefore, there is certainly a very great amount of new energy infrastructure based on new energy (power) producing technology that will be necessary to be developed and built to the necessary large scales along with a vast new energy storage infrastructure to support the worlds modern high energy intensity civilizations in the future. Creating and maintaining all this new infrastructure will necessarily require a very significant additional energy expenditure. The $64 x 1012 question: can all this be accomplished in time to avoid a catastrophic collapse of the world's modern civilizations with the net energy from the fossil fuels that still remain accessible? The alternative is too horrific to even contemplate!

No need to reply directly but I thought you might want to consider these issues and questions in a bit more detail in one of your future Blog postings.

Best regards, John King

Thank you for another informative web site. Where else could I get that type of information written in such an ideal way? I have a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.Solid Fuels

ReplyDelete